Compulsory Reading: Nofax Station Road Limited v The London Borough of Barnet

01/09/25

I’m sure this decision would have received more attention had it not been released at the end of July – although it is destined to be much quoted in future submissions to the Tribunal, it may not have been seen as a great beach read. But holiday season is nearly over so let’s get our brains back in gear…

Nofax packs a lot into its 20 odd pages…

- The first decision by the courts to consider the scheme cancellation rules in section 6A of the LCA 1961.

- Guidance on the level of detail required for the Tribunal to determine appropriate alternative development (AAD).

- The appropriateness of a before and after valuation distinguishing Ramac and applying the principle of equivalence and section 6A.

- “Grudgingly monosyllabic responses” from one expert witness after his evidence is “systematically dismantled” in cross-examination.

- But praise for the valuation experts for an “exemplary Statement of Agreed Facts” despite the Claimant’s assessment being more than 150 times greater than the AA’s.

Background

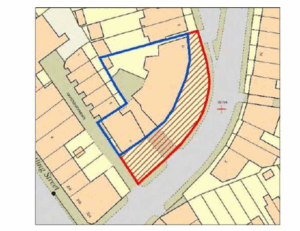

The background to the claim, and particularly the planning history of the site is rather complex but in summary, Nofax owned a 0.34 acre site located in Hendon near to the southernmost section of the M1. Around a third of the site (0.12 acres hatched red on the plan below) was acquired by the AA for road-widening under the snappily titled London Borough of Barnet (West Hendon Major Works) Compulsory Purchase Order (No. 2A) 2016. The valuation date was 1 November 2019.

Prior to that date, Nofax had redeveloped the retained land (outlined blue on the plan below) by constructing a 3/4 storey mixed use building comprising 22 flats with some office/retail space (subsequently converted into residential) with basement car parking. This development was under a 2012 planning permission. It is not clear from the decision whether that permission took account of the prospective road works but I assume it must have done.

Issues

There were three main issues before the Tribunal:

- What form of AAD would be acceptable absent the CPO scheme

- The valuation of the Site as a whole based on the AAD considered acceptable

- How to apply that valuation to arrive at an assessment of compensation and in particular whether a “before and after” approach should be used

By the end of the hearing, the Claimant’s assessment of compensation was £2.35m for the Rule 2 value of the land acquired and for severance/injurious affection (SIA) to the retained land based on a before and after valuation approach. The Authority considered that the rule 2 value of the land acquired was £15,000 and that there was no SIA to the retained land.

What form of AAD was acceptable?

It was common ground that the retained land and at least a part of the acquired land were capable of accommodating AAD at the valuation date. The Claimant originally proposed a 53-unit scheme. The AA proposed a scheme comprising 29 residential units (the Tribunal’s decision at paragraph 39 says 20 but this seems to be a typo) and 125 sqm commercial floorspace. The AA’s scheme appears to have been put forward in case it’s primary case (that the acquired land should be valued in isolation) was found to be incorrect.

The level of detail required for a AAD scheme

It’s fair to say that the Claimant’s planning expert did not have an enjoyable cross-examination. He was forced to accept that the Claimant’s scheme failed to comply with numerous planning policies and guidance including in relation to room dimensions, accessible dwellings, amenity space and parking. He responded by saying that no scheme is capable of complying with all policy requirements and that the criticisms of the Claimant’s scheme could be addressed by tweaking. In his experience, they would be resolved through discussions with the planning authority.

This gave rise to a discussion as to the level of detail required in order to assess AAD. The Tribunal noted that a reasonable planning authority would not expect the same level of detail as would be submitted for a full planning application. Whether the level of detail required was similar to that required for pre-application discussions with the authority or was more akin to those needed for an outline application was not, in the Tribunal’s view, important. There needed to be sufficient detail to demonstrate that the development complied with planning policy (failing which the claimant would have to show that any contravention would not be a barrier to permission being granted). Details which could be left to conditions (e.g. surface finishes, landscaping) do not have to be dealt with.

This is surely uncontroversial. Once a reference is made to the Tribunal, a claimant is in litigation. It has to put forward the scheme it wants the Tribunal to determine to be AAD in sufficient detail to allow the AA to respond to it. Certainly, tweaks can be made in response to criticisms from the AA but it is for the claimant to properly test options with its consultant and legal teams before a reference is made to the Tribunal. Of course, if a CAAD application is made to the local planning authority, there is nothing to stop the applicant having pre-application discussions (although where the LPA is also the AA, as here, we can understand there will be a reluctance to do so).

The purpose of AAD and the duty of an expert

The only important point about detail, as the Tribunal noted, is that AAD has no purpose other than to inform the assessment of compensation. There needs to be sufficient detail for a valuer to understand what values per square foot or unit to ascribe to the AAD and (where instructed) for a quantity surveyor to provide an estimate of construction costs and programme.

It appears that the Claimant’s expert did not understand this or his duties as an expert witness (our standard practice is to send instruction letters to expert witnesses which sets out the scope of their evidence and their duties – I don’t know whether that was done in this case).

Ultimately, the Claimant’s scheme was so deficient that the Tribunal could have no confidence in it. In cross-examination the expert “…resorted to answering questions with either grudgingly monosyllabic response, or with combinative questions of his own.”

The AA’s scheme was acceptable in terms of bulk and massing and was held to be AAD but this was the end of good news for the AA.

Commercial use and affordable housing

First, the Tribunal accepted that commercial space would not be required in that a policy requiring unsuccessful marketing of such space had previously been complied with by the Claimant. Instead of the AA’s 29 unit plus commercial scheme, the Tribunal held that a wholly residential 36 unit within the same massing would be acceptable.

Second, the Tribunal held that none of the units would need to be affordable. On the surface that seems a surprising conclusion given that the local plan required 40% and the Mayor of London’s threshold approach requiring 35% was being applied at the valuation date.

However, it was noted that the 2012 permission for the scheme on the retained land had not required any affordable housing and agreed by the valuers that the method of assessing viability would be based on a baseline land value – the higher of the EUV of the site plus 10% and development value. For the 2012 permission, the viability assessment (which happened to have been undertaken by the AA’s valuation expert) had stated that the baseline figure was £750,000 (in 2011). But there was no reliable evidence before the Tribunal as to whether that had changed by the valuation date. With no reliable evidence on baseline land values, the Tribunal was left with evidence as to what the Council was demanding from developers around the valuation date. Most smaller schemes, such as this one, were approved on the basis of 0% affordable housing and the Tribunal determined accordingly.

Valuation

Prior to the reference being made, when the AA was not represented by solicitors, both parties had proceeded on the basis of a before and after valuation. This approach seeks to assess both the rule 2 value of land acquired and SIA to retained land by deducting the value of the retained land in the scheme world from the value of the site as a whole (i.e. the acquired land and the retained land) in the no scheme world.

There was a significant difference between the parties even when the same approach was being used (£1.79m v £150,000) and the gap grew larger when the AA changed its approach to contend that a before and after approach was not appropriate as a matter of law. We’ll come on to that shortly.

The Claimant continued to utilise the before and after approach while the AA’s expert primary approach was to value the acquired land by itself. Since it could not be immediately developed, it’s value was limited to £15,000. It’s said in the decision that the AA valued the acquired land as a grass strip with only nominal value and no marriage value. If so, the assessment at around £125,000 per acre seems generous. The AA’s alternative approach was to assume that the existing buildings on the Retained Land were demolished, to value the Site as a whole and then to apportion value pro-rata by area.

Fortunately, little time was required to explore alternative valuations of all these approaches. In a statement of agreed facts described by the Tribunal as “exemplary”, the experts were able to agree that the compensation payable on the before and after approach would be £1.51m (£2.1m less £590,000). If the AA’s first approach was to be adopted, the compensation would be £15,000. A figure for the AA’s second approach was also agreed but does not appear to be stated in the decision.

Valuation principles

We now come on to the most controversial part of the Tribunal’s decision – the application of the law to the assessment of the compensation payable to the Claimant.

The AA argued that a before and after approach was only appropriate as a shortcut to assessment where it would result in a similar assessment to separate valuations of rule 2 value of the acquired land and of SIA to the retained land (if so, since one can only test that by undertaking separate assessments, it is unclear to me why one would ever take a before and after approach).

This is because, argued the AA’s counsel, rule 2 is subject to a number of statutory requirements e.g. the assumption of a sale in the open market by a willing seller and the no scheme principle set out in section 6A of the LCA 1961. No such provisions apply to an assessment of SIA under section 7 of the CPA 1965.

The AA referred to the Tribunal’s well-known 2014 decision in Ramac Holdings v Kent County Council (2014) which noted the different statutory regimes and stated that “Insofar as the claimant suffers a loss because of a diminution in the value of Retained Land then this will form a claim for compensation for severance and/or injurious affection. It does not justify adopting an artificial approach to valuing the Reference Land as if is still formed part of a larger whole.”

However, the Tribunal in Nofax distinguished Ramac on the basis that the facts were substantially different. As an aside, I’m a little surprised (although I’m sure there were good reasons) that there is no reference in the Tribunal’s decision to Hoveringham Gravels v Chiltern District Council (1978) which supported separate assessments of compensation for the value of the land acquired and for SIA (rather than a before and after valuation) and was subsequently applied by the Tribunal in Abbey Homesteads v Secretary of State for Transport (1982).

The Claimant’s barrister relied on the principle of equivalence. He said that in the absence of the CPO scheme, the Claimant would have been in the position of having a development opportunity across the Site as a whole with a significantly larger developable area. The Tribunal agreed, considering that the AA’s approach failed to reflect the principle of equivalence. The Tribunal acknowledged that its approach was somewhat artificial as it ignores the existence of the retained world scheme that had in fact been constructed by the Claimant prior to the valuation date.

Further, the Tribunal noted that section 6A(2)(b) of the LCA 1961 states that the second limb of the no-scheme principle is that:

“any decrease in the value of land caused by that scheme [i.e the scheme for which the authority acquire the land or the prospect of that scheme] is to be disregarded.”

Applying this, the Tribunal stated that the fact that the decrease predated the valuation date is not critical – and the construction of development on the retained land by the Claimant effectively crystallised the loss (although one might note that the valuation has to be brought forward to the valuation date). The Claimant is therefore entitled to compensation which reflects the loss it sustained as the owner of the whole of the Site by its inability to develop the Site as fully as it would otherwise have done.

I don’t know whether the AA intends to appeal the decision but if it doesn’t, I am sure that at some point some or all of the issues raised in Nofax will need to be considered by the Court of Appeal.